From 1976 to 2013, the price of college and universities dormitories increased more than 70 percent, on average.

From the years 1976 to 2013, housing costs rose modestly: About 5 percent for the typical homeowner or renter, adjusting for inflation. One quite simple explanation for this was characterized by Mark Twain years ago when he suggested: “Buy land, they’re not making it any more.” His words verbosely convey the simple concept that increases in development equal a decreased supply of land.

Unfortunately, there is a similar product for which drastically rising prices cannot be so simply explained. In the same 37 years measured for private housing costs, the price of college and university dormitories has risen, on average, by more than 70 percent.

{{tncms-asset app="editorial" id="fbf04fe8-8983-11e5-a6c3-2f7ad13b4b3a"}}

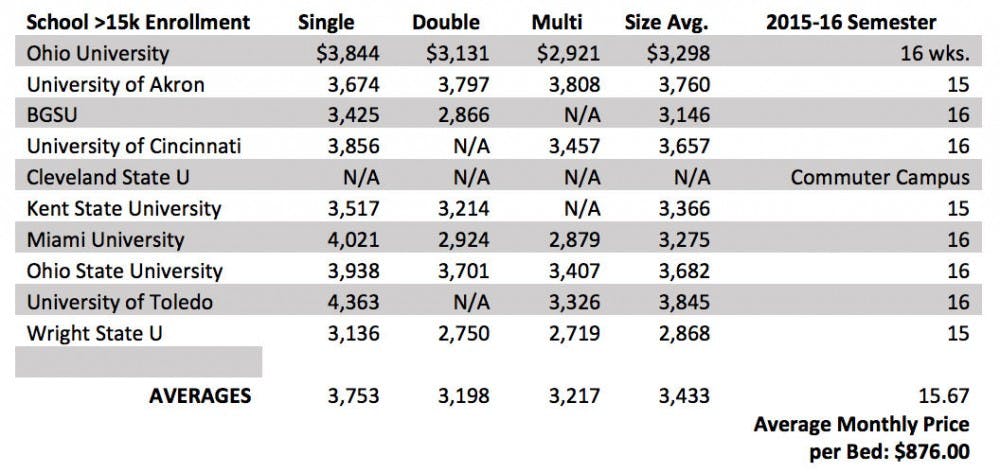

Housing prices at public, four-year universities in Ohio are terribly expensive compared to the alternative of third-party rental. In fact, the average price per bed at state institutions is $876 monthly, on track with the national price increase trends. One explanation for this suggests that dormitories have increased in quality of accommodations, however, new construction and modest renovations are quite commonplace in rental properties, as well.

According to market research conducted from the real estate database Zillow, the median rental price for a two-bedroom apartment in the state is $800, or $400 per bed. At less than half the price of dormitory accommodation, it is doubtful that rental properties provide less than half of the utility to residents, or that real operating costs are double.

The simplest theories, offered by professor Richard Vedder of Ohio University, cite operating inefficiencies of universities compared to private firms that specialize in certain sectors like housing or food service. Additionally, the monopolistic nature of university markets promotes “tie-in sales” that group two or more products and require they can only be purchased together.

According to The Federal Trade Commission, “the ‘tied’ product (dorms) may be a less desirable one that the buyer might not purchase unless required to do so, or may prefer to get from a different seller (private rental). If the seller offering the tied products has sufficient market power in the ‘tying’ product, these arrangements can violate the antitrust laws.”

It is reasonable to submit, given the facts, that university dormitories evoke the characteristics of a monopoly. It is an unnecessarily high price that millions accept each year with comparatively little reproach, while stories of climbing wall construction incite outrage and fuel political crusades against spending in higher education. Instead of distractions and anecdotal tokens of pressing issues, more effort could be put toward focusing on the more basal concerns in the same vein.

Trevor Marburger is a research assistant at the Center for College Affordability and Productivity.