Athens Code Enforcement doubles amount of trash tickets and fines during 2014.

If you were to ask what the most contested debate between Ohio University students and Athens city officials has been this school year, you’d likely get a garbage answer.

That’s because one of the year’s biggest controversies concerns trash.

More specifically, the trash-related tickets city workers have handed out, which fine students for everything from having a lawn covered in beer cans to an incorrectly placed garbage can.

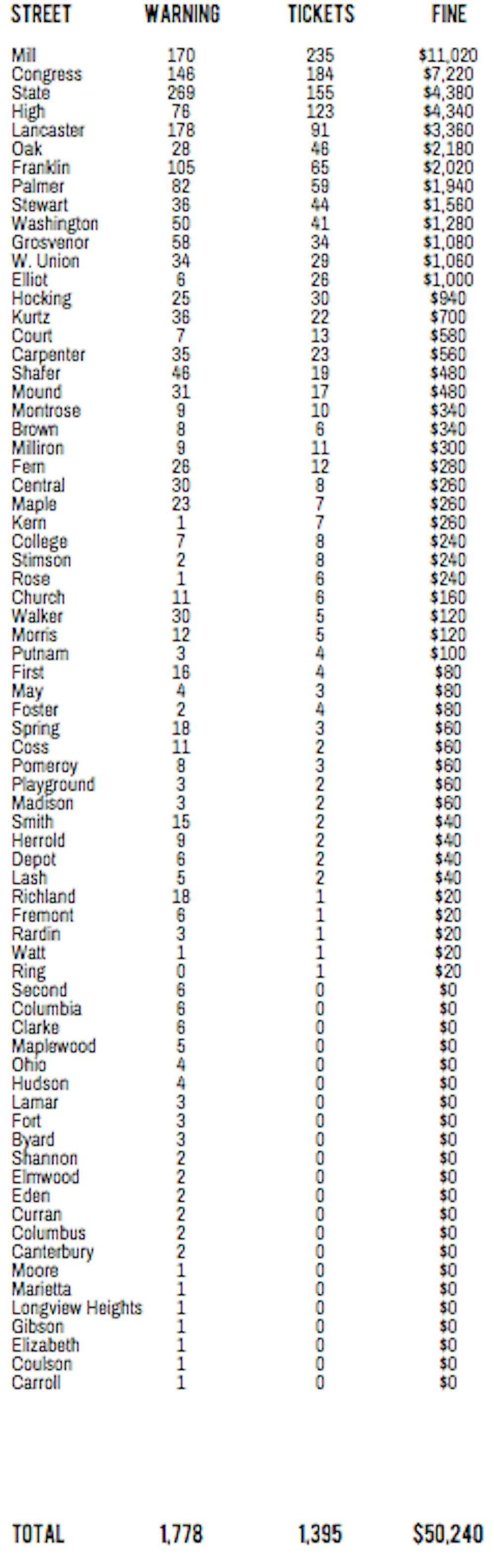

In 2014, Athens officials handed out nearly 1,400 tickets generating more than $50,000 for the city, in addition to roughly 1,800 written and verbal warnings, according to data from the Athens Office of Code Enforcement. Athens Code Director John Paszke said there are an additional 650 warnings and a handful of tickets that were not accounted for in the data his office provided, which stretched from Jan. 1-Dec. 9.

Students who live on Mill, Congress, State, High or Lancaster streets. are most likely to be fined, based on the data.

All of the top 25 most-cited streets had a large student population, and three houses — 45, 48 and 50 Mill St. — all topped $1,200 in fines for the calendar year.

“50 (Mill St.) is a fun house,” Paszke said. “We just continue to work with them.”

The number of citations has doubled from last year, according to code enforcement data.

That’s because George Nowicki, a relatively new, full-time waste litter control officer, has been at the job longer than those who preceded him, Paszke said.

“Let’s say you have one and he disappears for three months, whoever took over wouldn’t know the history of the house so they’d just warn them,” he said. “Now, we’ve got an officer who has been here for a while. He has history. Now, if he goes to a house for the fourth time, he’s saying ‘you’re getting a ticket.’ ”

Those tickets just increased for 2015 after Athens City Council passed an October ordinance increasing loose trash fines from $20 for initial tickets and $100 for fifth-and-subsequent punishments, with increases of $20 in-between, to $50 for initial tickets, $150 for fifth-and-subsequent offenses, and a $25 increase in-between.

Paszke said one warning is given for each property’s initial violation, however, a house can receive a warning for every first-time offense, so long as those offenses each relate to different areas of the city’s trash code.

That’s why some houses have as many as nine warnings with as few as three tickets, although it doesn’t explain how residences such as 2 and 2 ½ Elliot St. received no warnings and eight tickets — all within the 2014-2015 school year.

Trash warnings and tickets are supposed to reset with the start of each school year so that residents moving into a new house have the opportunity to start fresh, Paszke said.

But in about 50 instances, they did not.

In total, 875 different residences received at least one warning or one ticket in 2014, according to data. Although so many residences were ticketed, Paszke said the low-level tickets made little-to-no impact on students preventing further ticketing — and dirty lawns.

“(I) told (council) they started responding when the ticket reached $60,” he said. “You’ve got three tenants in a house to pay a $20 ticket, toss in $6 or $7 bucks and no one really cares.”

He insisted that the law isn’t targeting students. Rather, his employees spend most of their on-the-job hours patrolling areas of the town dominated by students, because that’s where they see the most action.

“Do we have to patrol every division the same? No,” he said. “That’s just us being realistic. But do we still go through those residential neighborhoods? Yes. There are areas we hit more than others — not because we’re targeting, but because that’s where the events occur; that’s where the parties are.”

He added that if a city worker finds one or two beer bottles on a lawn, they won’t write a ticket, although if they see those same two beer bottles a week or two later, they will likely write one.

“Bottom line is: You are responsible for your own property and you have to clean it up, even if someone else made the mess,” he said. “If you leave it laying there, even a small amount for a substantial period of time, you’re going to get a violation for it. It’s quite obvious some days when someone had a party the day before.”

Paszke reaches out to OU Off-Campus Housing and landlords when a property becomes one he repeatedly sees on his office’s reports, he said, adding that waste litter control officers are frequently cursed out on the job and he gets many vulgar messages on his voicemail.

“There isn’t a name in the book that he or I hasn’t been called,” he said. “They’re very vulgar. It’s not easy. It’s not always just from the students. Sometimes it’s from the parents.”

Athens Mayor Paul Wiehl said he wasn’t surprised by the findings of The Post’s data analysis.

“We just have a lot of people who don’t know how to put out trash,” he said. “It’s unfortunate that we have a lot of people who haven’t lived out in a neighborhood before and they don’t know how to contain their trash.”

Athens City Councilwoman Chris Fahl, D–4th Ward, said the increase in tickets could also be due to more complaints from residents.

“When I drive around, you can pick out the student houses,” she said. “And I live in a mixed neighborhood.”

Wiehl also didn’t think students were being targeted; rather, the waste litter control officer was just going to the areas where trash was most present.

“Probably, most don’t think it’s necessary; they don’t have to clean up,” he said. “I guess it’s part of the learning process outside of the classroom.”

{{tncms-asset app="editorial" id="f304a5a2-a5d4-11e4-9741-7b65e32bc187"}}

@akarl_smith

as299810@ohio.edu

Read more:

{{tncms-asset app="editorial" id="a89d9c14-a5aa-11e4-88e3-47ecc152661b"}}