Athens and Ohio University officials reflect on the infamous public sex act on Court Street from last year’s Homecoming Weekend

Editor’s Note: We will be running a series taking a look at sexual assault in and around Athens and Ohio University throughout next week.

No one was prepared for the media circus Athens would turn into after two students engaged in a public sex act outside of Chase Bank, 2 S. Court St., during last year’s Homecoming Weekend.

In the wee-morning hours of Saturday, Oct. 12, 2013, two Ohio University students performed oral sex in front of the bank as the uptown bars were closing. Soon, a crowd of people gathered around. Some began filming.

And then some of the footage was posted online. On Oct. 13, the still unidentified woman involved filed rape charges against the still unidentified man.

The story was covered locally, then throughout the state. Days later, the story had made it into the Associated Press, New York Daily News and the Daily Mail of London, among other prominent publications and television outlets.

And the story affected the lives of those far removed from the public sex act.

Rachel Cassidy, a sophomore at the time, was attacked by Internet trolls around the world claiming she was the woman who had filed “false” rape charges.

OU Dean of Students Jenny Hall-Jones would go on the record and say Cassidy had no involvement with the university investigation of the public sex act.

“I would still do the exact same thing again,” she said Tuesday. “I wouldn’t have changed a thing about that. But, because we did that, I ended up getting hate myself, and I kind of shut everything out.”

Then, there were those who caught heat for posting the video of the alleged rape online. With anonymous posting apps Yik Yak and Unseen gaining popularity on campus, students might now feel less responsible when posting something damaging online.

Hall-Jones, who is on Yik Yak, said she believes people are being more careful about what they post on social media — even anonymously.

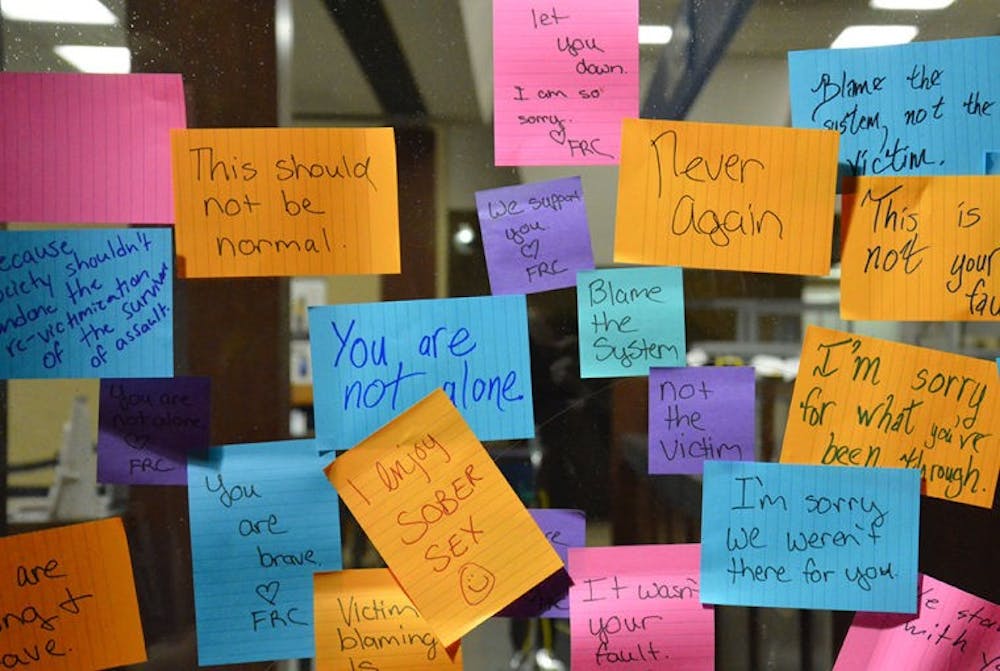

Another incident to gain attention in the aftermath was an interaction between Neal Dicken, an Athens Police officer, and students who were posting notes on Chase Bank in support of the accuser.

“He asked us ‘Why are you doing this? What’s the point? All you’re doing is tearing the town apart,’ because Athens was getting negative media attention,” Emily Harper, a 2014 graduate of OU, said. “He was saying we were a part of the problem.”

In spite of all that — and even as a grand jury decided there was not probable cause to pursue the rape charges — the year that followed included a campaign to spread awareness, advocate for survivors and educate students, faculty and officials on sexual assault.

“I think that was the silver lining of this happening last year,” Hall-Jones, said. “I think the shift you’re seeing is other people (outside the administration) having that conversation. It’s a very positive shift.”

Athens Police Chief Tom Pyle said there has been quite a bit going on in the background regarding how the department interacts with sexual assault survivor advocates throughout the past year, although nothing official has been put in motion yet. He said, since the incident last Homecoming, there remains a disparity between advocacy and law enforcement.

“Advocates have no responsibility to enforcing the law, and therefore they’re entitled to their opinions based on just that, their opinions,” Pyle said. “Our opinions in law enforcement are forced by how the law reads and what’s required by previous case law.”

It’s not that police don’t believe survivors or don’t understand the situation, he said, it’s that the law officers are sworn to enforce is, at times, at odds with the advocacy viewpoint.

“The truth is, it’s not personal, and it’s not what the advocates sometimes make it out to be — insensitive,” he said. “The problem is the law, not law enforcement.”

He isn’t sure how the law could be changed to bridge the gap between police and advocates.

“Sexual assault is a specific intent crime,” he said. “We have always had difficulty proving consent and specific intent. I’m not sure if you would be able to pass a law that adequately addresses advocates’ concerns.”

He added the toughest thing to deal with in the weeks following the public sex act was the national media, but he wouldn’t change how the department handled the situation.

“I’m not sure we had the opportunity to change a lot,” Pyle said. “Minds were made up, so we had some pretty extreme viewpoints going on a global scale.”

Hall-Jones said she would have been more active on social media, if she were to re-live the immediate aftermath.

“My knee-jerk reaction was to be more silent,” she said. “(Being more outspoken) is a good lesson for me to remember.”

Protecting the identity of those involved was one of the hardest parts Hall-Jones dealt with, she added.

“All we can say is we are actively pursuing an investigation, and all we could explain was the process,” she said. “But that wasn’t what people wanted.”

@akarl_smith

as299810@ohio.edu