In the spring of 1973, a talented Ohio baseball team finished second in the Mid-American Conference. Four student-athletes on that team would eventually break into professional sports.

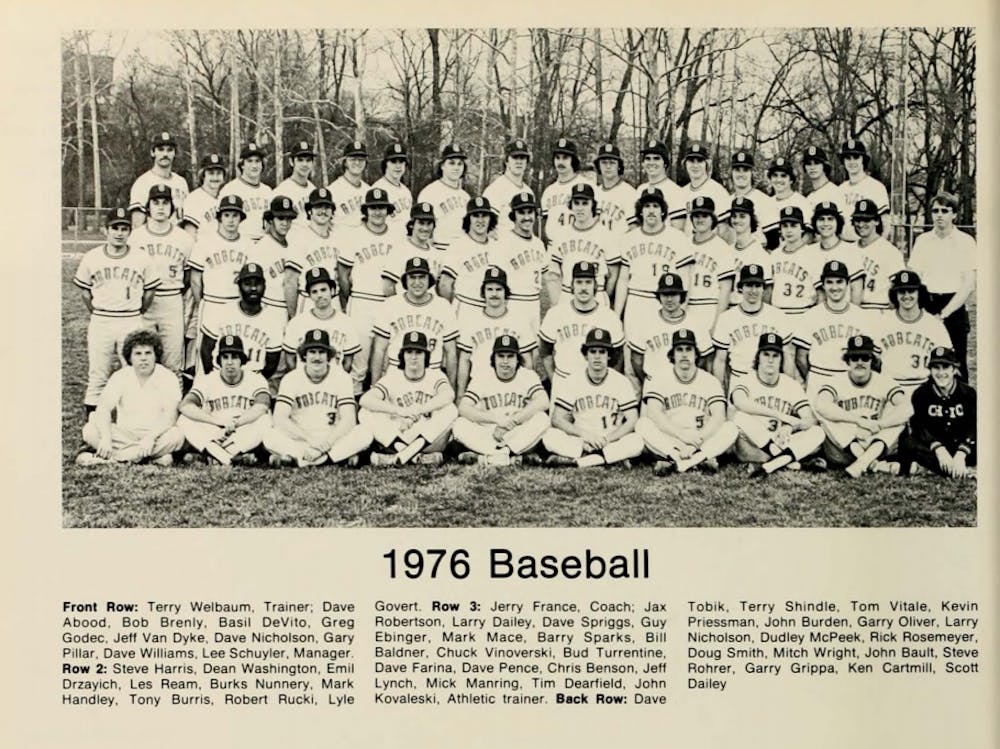

There was Steve Swisher, a catcher who enjoyed an eight-year major league career and an All-Star bid in 1982. There was Dave Tobik, a right-handed pitcher who was the second overall player selected in the 1975 MLB Draft. There was also Bob Brenly, who was an All-Star catcher with the San Francisco Giants and who eventually won the World Series with the Arizona Diamondbacks as a manager in 2001.

But then there was Basil DeVito.

DeVito, a walk-on with the Ohio Bobcats that spring, came to Athens specifically to play baseball but rarely saw the field.

He wasn’t a star athlete, but about 30 years later, he found himself as the head executive of arguably the most notorious sports league that ever existed: the XFL.

* * *

Originally a Latin major, he switched to journalism after a word of advice from his academic adviser.

“Is your plan to go back to your high school and teach Latin and coach baseball?” Devito said his adviser, professor Tom Peters, asked of him.

He switched majors and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in journalism in 1976.

While still in his undergrad, DeVito created an old Athens favorite, which he now thanks for his ascent into the business world.

In the spring of 1975, his junior year, he began working at The Junction — now known as J Bar. There, he created the promotion 'Quad Night,' where four shots were sold for $1.

That was his first taste of the business world. After graduation, he spent a year in the sales division of Procter & Gamble in Chicago in 1977. One year later, he was admitted into the graduate sports administration program.

“At that time, there weren’t many programs around," DeVito said. "It was very challenging to get accepted to. There was a much greater demand (for the program) than slots. I think what it did was provide me with a mindset that if you’re going to accomplish something, especially in the realm of sports management, it’s going to be a process."

DeVito graduated with a master's degree in sports administration in 1978. He went on to complete an internship in the NFL league office under commissioner Pete Rozelle. He then spent time with the NBA’s Indiana Pacers and Detroit Pistons as well as a local television station in Indiana.

In 1984, he helped produce and package an exhibition game between the U.S. Olympic basketball team and the NBA All-Stars. Almost 68,000 people attended the game, the largest crowd for an indoor basketball game at that time.

One year later, however, he was introduced to the man who would forever change his life.

* * *

In 1985, DeVito became the 16th employee at a company that was just relocating their offices to Stamford, Connecticut.

He had been hired as the director of promotions for the World Wrestling Federation. His new boss: Vince McMahon.

At the time, McMahon was planning for the first production of WrestleMania, which took place at Madison Square Garden.

As McMahon built the then-WWF — now WWE — into a sports entertainment empire, DeVito was beside him and headed up the organization’s marketing.

The marketing for the WWE has long been the envy of sports leagues across the globe. Millions of people tune into their weekly programming and pay-per-view events, including WrestleMania, which made $17.3 million last year and was seen by 101,763 fans live, both record numbers for the company.

“If you look at the history of sports entertainment, they’ve done an unbelievable job,” James Kahler, the executive director for the AECOM Center for Sports Administration at Ohio University, said.

With the success of WrestleMania, the company’s popularity boomed in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Names of wrestlers such as Hulk Hogan and Stone Cold Steve Austin became household names.

DeVito’s boss was no small part in their success.

“(McMahon) is clearly the best motivator I’ve ever been around,” DeVito said. “He is a visionary.”

In 1999, WWE went public, and its initial public offering was valued at $172.5 million.

That same year, McMahon, who is now valued at more than $1 billion, announced a new venture that would define the company for years to come –– and dramatically reshape DeVito’s career path.

* * *

Standing at midfield of Sam Boyd Stadium in Las Vegas, McMahon wore a leather jacket embroidered with the new XFL logo.

A sold-out crowd watched the exuberant businessman lift his arms and shout in his trademark Mr. McMahon voice, "This. Is. The. XFL!"

The XFL, which is not an acronym, was announced in 2000 as a strategic partnership between the WWF and NBC. Its new president was DeVito.

The league tried to combine the popularity of professional wrestling and football. It branded itself as a more outrageous form of football, opting for scrambles instead of coin tosses and ridding the league of fair catches. Players were also allowed to use whatever name they liked on the back of their jerseys, typically where last names would go.

Running back Rod Smart used the phrase "He Hate Me" on the back of his jersey, which became one of the most popular nicknames in sports history.

The league used scantily clad cheerleaders in commercials and, at one point, told fans they were going to put a cameraman in their locker room.

DeVito was in charge of day-to-day operations of the fledgling league, designed to develop it into a legitimate competitor to the already-popular NFL.

“It was a significant departure from what I was doing,” he said.

The league, which was evenly co-owned between the WWF and broadcast partner NBC, held its inaugural season in 2001, with the first game taking place between the New York/New Jersey Hitmen and the Las Vegas Outlaws. Each team was owned and operated by the XFL, which meant DeVito had a large responsibility

The league started with impressive TV ratings, but by the end of the season, ratings fell. They hit a dreadful low during the end of March 2001, when their weekend programming received a 1.6 rating, the lowest-rated program on a major network in primetime history.

In May 2001, the XFL closed, less than four months after their inaugural game. DeVito was the one to deliver the news to all eight clubs.

Steve Becvar, an Ohio alumnus, was the vice president of marketing and sales of the Memphis Maniax at the time.

“When (the call) came,” Becvar said, “you just felt your body become something you’ve never felt before. A lot of emotion.”

DeVito had scheduled a conference call with all of the teams on May 10 at 5 p.m.

“I want to thank everyone for all their effort,” Becvar recalled DeVito saying in the conference call. “For their work and commitment. As of Monday, the league (will) cease and desist. We’ll get back to you with severance information and the next steps.”

McMahon labeled the league “a colossal failure." However, as DeVito looks back 16 years, it was anything but.

“It was the greatest thing in the world,” DeVito said.

* * *

16 years after the failure of the XFL, DeVito is back with McMahon and the WWE.

He now serves as the senior advisor of business strategy for WWE and is a member of the board of directors for the company. DeVito also owns a small minority stake in the company.

Following the league’s closing, he worked in horse racing with the National Thoroughbred Racing Association and the Breeder’s Cup.

DeVito returned to the WWE after McMahon approached him about an idea for creating

Soon, however, he’ll be able to relive the days of the XFL.

On Thursday, ESPN will air “This Was The XFL” as part of their 30 for 30 documentary series. The film is directed by Charlie Ebersol, the son of Dick Ebersol, who was the chief executive of NBC Sports and worked alongside McMahon in forming the league.

The film will focus on the relationship between McMahon and Ebersol, the failures of the league and some of its lasting successes.

The league’s successes are what DeVito carries with him 16 years after the league’s closure.

Even though the XFL has gone down as one of the most notable failures in sports history, DeVito still holds the league as a success in his mind.

“There were a lot of times people thought we were crazy,” DeVito said. “Ultimately, there were a lot of things we did right that do live on today. I did learn it’s OK to have a stretch goal and even when most of the world is telling you that you have no chance.”