“I feel like I’m the richest woman in the world because I do whatever my brain conjures up,” said Annie Warmke, a homesteader from Blue Rock Station in Philo, Ohio.

What Warmke is referring to is building and creating things for her home and living a life off the goods of mother nature. She is what could be referred to as a modern homesteader and is portrayed in the exhibition curated by Elizabeth Thompson dealing with romanticizing and questioning rural life.

From the countryside of Pawhuska, Oklahoma, herself, Thompson felt the urge to dig deeper into the contradictions circulating around people outside the urban space. So, the 55-year-old started researching and writing a chapter for a book called “Rural Womanhood,” published in 2021.

“What I was seeing is that there are nightmares and there are fantasies about what it means to live in the rural part of the United States,” Thompson said. “So, what I wanted to get was the truth … of what it meant to be a rural woman living in America today.”

Thompson’s findings are currently exhibited in the Kennedy Museum of Art in Athens, 100 Ridges Circle. Her exhibition, “Homesteading Women: Past, Present, Near and Far,” opened in September and will remain on display until mid-March next year. In a small room in The Ridges, current and historic photographs, quotes and fabrics surrounding homesteading in Southeast Ohio are displayed and contrasted with one another.

“I use this word 'homesteading' because it’s kind of a catch all phrase,” Thompson said. “Technically, homesteading refers to people who are making most of or a lot of their own food. They’re gardening, milking cows, they have chickens, they’re gathering eggs. And they’re getting close to being self-sufficient.”

Thompson said that not all women she interviewed would technically qualify as homesteaders but most of them get pretty close.

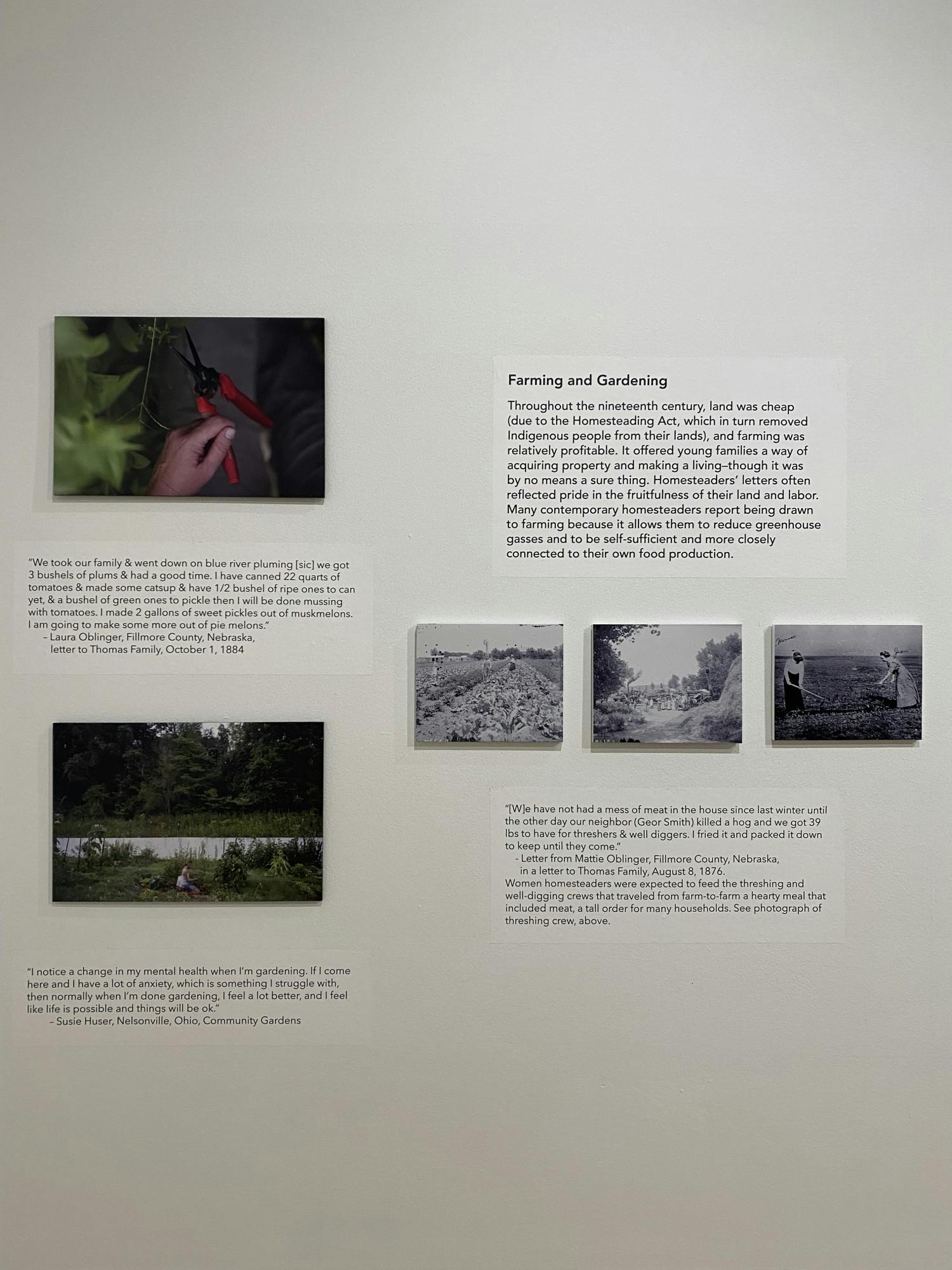

Using that terminology, Thompson and the exhibition draw on the Homestead Act of 1862, which granted many Americans 160 acres of public and rather inexpensive land. The Act granted land claims in 30 states, which forced many Indigenous communities westward, decreasing buffalo numbers and implementing unsustainable farming methods, as many of the settlers did not necessarily have a background in agriculture. The Act played a crucial role in the U.S.’s westward expansion and, opposite its harmful nature toward Indigenous Nations, was otherwise groundbreakingly inclusive, allowing women, immigrants and formerly enslaved people to own land. The only group excluded from the Act were people who had aided the Confederacy.

“Athens is such a mecca of homesteaders and farmsteaders,” Thompson said. “Athens has such an impressive farmers market and such an extensive community of people who are engaged in that kind of environmental, sustainable work, so I thought it would be appealing to people in Athens to spotlight some of these farmers and women. I also thought it would be a way of honoring these folks who work so hard and are doing it for their families, but also to improve the climate and to help mitigate climate change.”

Thompson said she lived in Athens as she pursued an academic career and worked as an associate professor of instruction in the English department of Ohio University for many years, before she was laid off as a result of financial shortfalls caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021. While her fascination for American literature and academic work is undeniable when she speaks about her research focus and her studies in a soft voice filled with admiration, Thompson was able to take her knowledge and transcend it into other fields as well.

Making the best out of that unfortunate situation, she applied for a guest curator position at Kennedy Museum of Art and got it.

“As I was writing the chapter, I kept seeing all these photographs and I thought, ‘Wow, it would be really wonderful to share these,’” Thompson said.

With her background in academia in mind and a prior focus on early American settlement and the representation of Native American women, Thompson chose a comparative approach to her first ever exhibition.

“I’ve always been interested in museums, and I’ve always tried to use museums in my classroom,” Thompson said. “It seemed to me like it was a very visual project. I really liked the idea of the juxtaposing of historical and contemporary.”

Her own upbringing played a huge role in leading her work into the direction it is at now.

“One thing I can tell you is that I grew up in rural regions of Oklahoma,” Thompson said. “I always had a lot of interest in music and culture and was eager to get out of Oklahoma.”

Thompson grew up in Pawhuska, which she described as the headquarters of the Osage tribe.

“I always felt as though I was just passing through,” Thompson said.

And although she left Oklahoma behind, she said it never really left her. She described how she started researching her family roots on ancestry.com.

“What I found is that my ancestors were homesteaders,” said Thompson. “It wasn’t just a couple of them, but many, many of them.”

Thompson describes herself as an avid gardener, something she believes must be in her DNA. Her personal connections to the history of farming and of homesteading help frame her passion for the subject. Thompson’s gentle, soothing voice does not give away too much excitement about the topic. Only her never-ending urge to talk about her achievements underlines her passion.

Binding all her research interests, experiences and her own story together, Thompson curated the exhibition for the Kennedy Museum. Divided into five parts—Building and Creating, Home, Farming and Gardening, Raising Animals and Raising Children—the exhibit juxtaposes the perspectives of women who lived in Nebraska, Montana, Oklahoma and North Dakota from 1862 to 1920 and those of six Appalachian women getting close to what could be considered a modern form of homesteading.

“We offer these stories to educate, dispel stereotypes, highlight the diversity of today’s rural women, and help narrow the urban-rural divide,” Thompson wrote in a text that can be found on the walls of her exhibition at Kennedy Museum.

Putting together the exhibition, Thompson asked herself essential questions, like what it means to be a real woman today.

After she lost her job at OU, a lot changed for Thompson, and she raised the question of what she really wanted in life.

She remembers that she has been really interested in meditation and mindfulness the past 25 years.

“I wanted to go somewhere where there would be a beautiful environment, beautiful location, focus on education,” Thompson said.

Today when she’s not guest curating, she works at a Buddhist meditation retreat center in central Massachusetts.

“Do whatever you want to do,” Thompson said. “You don’t have to feel stuck.”

Ultimately, Thompson would like to combine mindfulness and teaching at a college but also get back to writing. She said she values the career she pursued before and appreciates what she learned in academia, but in the meantime, is grateful to educate in other ways, including through her exhibit.