At nearly 60 years old, Athens resident Kenne MacKillop still remembers a love from adolescence — food. MacKillop became interested in cooking as a teenager, making meals for family and exploring new recipes. That enthusiasm sparked by food, however, became more elusive as MacKillop grew older and gained independence.

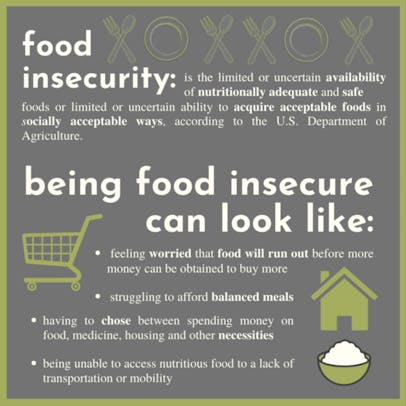

Throughout adulthood, MacKillop has experienced food insecurity due to a number of compounding health and financial factors.

MacKillop’s experience with food is not uncommon. In Athens County, approximately 19% of residents — or about 12,500 people — are food insecure, according to 2019 data from Feeding America. That number is 5% higher than the rate of food insecurity in Ohio and nearly double the national rate.

“We are the world's richest country and have people struggling for resources — basic resources,” such as clean water and healthy food, Theresa Moran, former director of Ohio University’s food studies program and current Athens advocate for equitable food access, said. “That, to me, is a real problem.”

During the past two years, that struggle to obtain food has intensified due, in part, to the COVID-19 pandemic, supply chain disruptions and inflation. Food prices are rising at a rate much higher than other commodities, such as housing or transportation. Since November 2020, the cost of grocery store or supermarket food purchases has risen 6.4% nationally, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Consumer Price Index. If a gallon of whole milk cost $3.50 in 2020, it would now be priced at approximately $3.72 today.

Nationally rising costs of food are felt locally, too.

“Buying things that are going to satisfy my longing for something good is a challenge for my budget,” MacKillop said.

For MacKillop and nearly 12,500 other Athens residents, food insecurity disadvantages their physical health, mental capacity and, for students specifically, academic performance. There are a number of resources present, both at OU and within Athens, aimed at combating the effects of food insecurity. Though helpful, the food resources’ impact is limited by stigma around accessing them and the understanding of food insecurity as a symptom of broader societal issues.

Feeling the effects: Athens residents

Food insecurity is not a singular experience for people living in Athens. One of the most identifiable characteristics of food insecurity is hunger, which can be an effect of a multitude of intercausal factors. Some contributors to food insecurity include: unreliable access to transportation, low wages, other expenses like housing, limited cooking facilities and the absence of nearby retailers that sell affordable, nutrient-rich foods, according to healthypeople.gov.

Without consistent access to adequate amounts of nutritious food, people’s physical and mental health suffer. People dealing with pandemic-induced food insecurity were at a 257% higher risk of anxiety and a 253% higher risk of depression than their food-secure counterparts, according to a December 2020 study led by Di Fang, an agricultural economics professor at the University of Arkansas. Food insecurity and the high cost of food can force people to make undesirable decisions — pay the next college tuition installment and not have enough food for the next month or buy a sufficient amount of groceries and risk having to drop out of school, for example — increasing mental distress.

That stress coupled with the inability to purchase nutrient-filled, sustaining food takes a toll on the body, too. Healthypeople.gov reports obesity and chronic disease as being more prevalent in food-insecure populations.

“Food insecurity is not just that people are lacking food,” Moran said. “It's the cascading effects (of) not having food and then not being properly nourished.”

Food insecurity can exacerbate pre-existing health issues and can lead to new conditions developing, creating a cyclical pattern of illness stemming from a lack of consistent access to nutritious food.

“I have chronic pain issues, so anything that triggers chronic pain is something I want to avoid,” MacKillop said.

Riding the bus to a grocery store, navigating the store to find food and preparing meals are activities that can make MacKillop’s chronic pain flare up. When MacKillop’s chronic pain is triggered, it is often accompanied by “emotional pain” that further strains MacKillop’s ability to complete tasks and remain mentally well.

“I have a lot going on,” MacKillop said. “I think it's true of a lot of people for whom food insecurity is chronic. There's underlying problems.”

Feeling the effects: OU students

College students are a subset of the Athens population disparately impacted by food insecurity. While the rate of food insecurity in Athens is close to 20%, a survey of OU students found that more than a quarter of respondents experienced food insecurity.

Students face an additional symptom of food insecurity: decreased academic performance. Students experiencing food insecurity “are about three times less likely to be among the highest 10% GPA compared to their food secure counterparts,” according to a 2019 article published in the Journal of American College Health.

Not having enough food detracts from students’ ability to focus on school. Some work an extra job in an attempt to make enough money to afford food, lessening the time they have each day to devote to schoolwork. Others are limited by decreased energy levels and mental clarity that can accompany inadequate food consumption.

“Studying in school should be your priority, not having to worry about where your next meal is or making sure that you have a balanced meal because you're trying to make your budget work in order to have that,” Charlie Fulks, basic needs coordinator for OU’s on-campus food pantry, Cats’ Cupboard, said.

Many attend college in hopes of increasing future possibilities for jobs and, ultimately, a secure life. But in trying to achieve that, approximately a quarter of OU students encounter an additional challenge in accessing food to nourish their minds and bodies.

Seeking help and facing stigma

Resources that allow people experiencing food insecurity to combat the financial burden created by rapidly rising food prices exist on OU’s campus and throughout Athens. The Southeast Ohio Foodbank receives donations and distributes food to 11 pantries, community meal makers and other organizations that give groceries directly to individuals throughout Athens County. Cats’ Cupboard, a food pantry specifically for OU students and staff, is similarly sustained by donations.

Direct monetary support from the federal government can also aid those who are food insecure. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, allows recipients to utilize a monthly deposit of money via electronic benefit transfer card to purchase “healthy” foods from specified retailers.

During the pandemic, qualifications for SNAP eligibility expanded, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Among the groups benefited by SNAP’s expansion were college students. Any college student who is eligible to participate in state or federally financed work study or has an Expected Family Contribution of 0 is qualified to apply for SNAP benefits.

In Athens County, approximately 60 stores accept SNAP benefits, according to the government-produced “SNAP Retailer Locator.” Fourteen of those retailers are within a 2-mile radius of OU, and one of them is Jefferson Market on OU’s campus.

“A lot of college students are eligible for SNAP, and they just don't know it,” Lydia Dunn, a SNAP outreach worker with the Southeast Ohio Food Bank, said. “And a lot of people are embarrassed to admit it.”

Stigma and unawareness create barriers for people, especially college students, to access support. The culture of food in college, to an extent, constructs food insecurity as “normal,” Dunn said.

In fact, until recently, university students were not included in conversations about food insecurity. It was thought that if students were able to afford a college education, they must also be able to afford food, which is not always the case.

“I think there's this big idea like, ‘Oh, I'm a college student. I just eat ramen. That's just what college students do,’” Dunn said. “You don't have to. You can get help; you can utilize resources so that you can have a healthier diet, and you don't have to eat ramen every day.”

Stereotypes surrounding SNAP also can deter recipients from using the program. MacKillop has encountered judgmental reactions from store clerks when using government benefits to purchase certain foods.

Throughout MacKillop’s life, homelessness and residence in public housing have restricted opportunities to cook and store “healthy” foods.

“Someone would see me buying candy or chips with my food stamps and be like, ‘Hey, when I was a kid, we had to make food stamps last,’” MacKillop said. “Well, dude, I don't have a home to go to to cook up a nutritious meal. And when I have a place where I can stay and cook, it’s not easy. Now that I have a home, I find that I'm just exhausted all the time, and cooking is hard.”

Looking at systemic issues and envisioning local solutions

Current solutions to food insecurity try to provide food to people who do not have it. While that certainly curbs the effects of food insecurity on individuals, it does not necessarily address the underlying, larger-scale causes of the issue, such as inflation, low wages and supply chain disruptions.

“This is not a one-shot deal. It's not a box of food and done,” Moran said. “It is fundamental work to change the food system to make it more accessible and equitable.”

MacKillop envisions a future system that focuses on local, collectivized food production. Communities understand their needs and wants better than outside groups. Returning the task of food production to the people who will eventually consume it could be empowering, MacKillop said.

Fulks also emphasized the need for local approaches in addressing food insecurity as a multifaceted issue.

“If everyone kind of focuses on their little place and their community then, slowly, we can all get access to food,” Fulks said.

Approximately one-fifth of Athens’ population is food insecure, but the effects of insufficient nutrition and limited food access are not contained by the county line.

“This deprivation, being deprived of a basic human need, and I would say a basic human right, just amplifies every other challenge in our society,” Moran said.