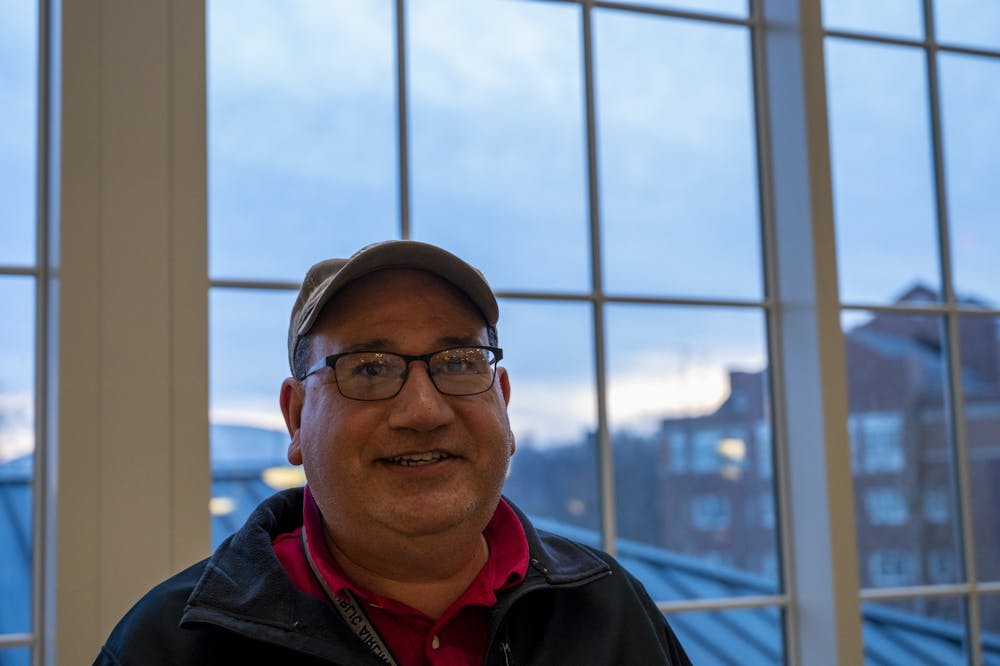

Wearing a striped polo shirt, cargo pants and a brown cap, Bill Beamish can’t hide his nerves as he takes the stage in The Front Room. With a mic on the stand in front of him, his right hand quivering, he struggles to read the scribbles on the crumpled sheet of yellow paper he holds.

His notes fill the entire sheet, a script for the jokes he intends to tell in his first performance with Blue Pencil Comedy, a student organization at Ohio University.

“I’m going to use these notes,” Beamish tells his audience in a thick New York accent. He clumsily smacks his chin against the mic, sparking laughter from the dozens of people in the dimly lit room of blue and white lights.

“I’m gonna go back and forth,” he says. “I might not be perfect. Is that OK with everyone?”

People nod and smile, but an uncertainty hangs over the room like a rain cloud for this first-time performer.

Nobody knows how he’ll handle the spotlight. Will Beamish, a pudgy, 48-year-old native of Brooklyn, bumble his way through his five-minute set, or will he leave his live audience on this last Saturday night in February in stitches?

***

Beamish became a fan of comedy in the 1970s and ’80s.

He watched some of the most famous comics — Eddie Murphy and the late George Carlin were his favorites — from a couch in his suburban summer home in Bay Shore, New York. He also claimed to have once tossed a Frisbee on a Long Island beach with comedian Mel Brooks.

Comedy always intrigued Beamish. He picked up a knack for improv while he was an AT&T salesman in the ’90s and frequently made business owners laugh on the other end of the telephone or in meetings. Beamish remembered he was nervous for those, too, even though he found a way to crack a smile.

When he’d enter a client’s office, Beamish tried to spot something he could relate with. If he saw a golf club, he told a story about the time he played a nightmare 18 holes on some course. If he spotted a mini-taxi figurine, he talked about the miserable, smelly, no-good cab he rode in on his way to the meeting.

“I just needed to find something,” Beamish said. “Anything. If they’re not talking, they’re not going to buy anything.”

Beamish seemed to find a way to connect with someone’s funny bone, but he never seriously considered a career as a comedian. Not then. He didn’t want to stay in sales, either. Instead, he wanted to become a pilot.

The latter was what brought Beamish to Ohio University. He came to campus in 2009 to earn a doctorate in education and become a flight instructor.

But he didn’t ditch his interest in comedy.

That’s why he lingered outside Front Room, a campus coffeehouse, in 2016 when he heard people laughing. He wandered inside, and he spotted a sign that read: “Blue Pencil Comedy -- Saturday at 8 p.m.”

He found a seat near a high-top counter along the windows and didn’t leave. He has been a frequent attendee at Blue Pencil events since. He has enjoyed watching students, most young enough to be his son or daughter, crack jokes and make him laugh.

Beamish itched to put his improv talent to the test. Could he do it on a stage with bright lights and dozens of people focused on every word? He was unsure.

Two weeks ago, the potential embarrassment of bombing hit Beamish when one participant went on stage and said … nothing.

Well, the wannabe comic tried to talk, but no one laughed. Not for a second. If anyone found his act funny, it’s because they were laughing at him — not with him.

“‘Oh s---,’” Beamish said to himself. “Maybe I’m going to do that.”

His New Year’s resolution was to try, so he joined Blue Pencil.

“This is the year,” he told himself. “It’s 2020, and I gotta do it.”

***

Beamish entered the conference room in Baker Center, sat in the first seat he saw and waited for nine other members of Blue Pencil to show up.

He had arrived early to flip through his notes and place a bag of props next to his seat. He still had questions — lots of them — and didn’t want to leave the conference room, which soon filled with OU students much younger than he was, without answers.

Delaney Murray, president of the comedy club, sat across the table and tried to provide them.

“When we flash the light, that means you’re four minutes through your act,” said Murray, a senior and a veteran of the Saturday comedy show.

“So I have four minutes?” he said.

“Yep,” Murray replied.

She explained how she shines a flashlight from her smartphone at the fourth and fifth minutes of each act to signal time limits. After the fifth minute and a second flash, which is done while she waves the phone, performers must end their set as soon as they can.

“I didn’t bring a stopwatch,” Beamish said.

“It’s totally fine,” Murray said. “It’s our job to keep track of time, and it’s your job—”

“You’ll do that for me?” Beamish interrupted.

“Yes,” she said with a smile and a nod. “It’s your job to just enjoy your performance.”

In the conference room, Beamish had two minutes to practice his set as if he were in front of The Front Room audience. The executive board of Blue Pencil, a club that has been around for over two decades, wanted to ensure he could carry out his plan. It didn’t matter how ready Beamish was; he was going to perform. Blue Pencil always let first-timers perform.

He slammed an unopened beer can on the table.

“It’s a beer can with my name on it,” he said. “A stout, actually.”

The beer can was a prop. Murray told him the prop was fine if he didn’t drink the beer.

“No, no, I don’t want to drink it,” he said with a worried look. “It’s been in my family for almost 30 years.”

Now, it was time for his run-through. Beamish shuffled his notes and grabbed the beer can.

“Um, well, my name is Bill Beamish,” he said. “When I studied as an undergraduate, people didn’t believe …”

He stopped. Murray and the eight others in the room smiled to signal encouragement.

“Wait, no,” he said. “Let me start over.”

He recited the line again and then told a story about himself. He said he came from a family that owned a beer company. When he mentioned that fact to friends, none of them believed him. He told them to Google it. They did.

But where was his joke?

The exec board wasn’t sure.

Neither was Beamish. At least not at first.

“Was that the right way to say it?” he asked.

“Just do it like you’re on stage right now,” Matthew Connel, one of the board members, said. Connel smiled and moved his hands to encourage Beamish to keep going.

“Well, I’m from New York,” Beamish said. “And I, uh, when I first moved here, I … I got a lot of speeding tickets. It was annoying, and I spent a lot of money.”

Beamish paused for a second, as if waiting to hear a response from the room. Everybody stayed silent except Connel, who seemed to laugh out of pity.

Beamish kept going. He ended his test run with a story about how he drove his car over the sidewalk on a roundabout in Athens after waiting for an old lady to realize she was driving the wrong way.

That tale drew a few laughs, though they didn’t seem sincere.

“I think that’s probably enough time for right now,” Connel said.

“Oh,” Beamish said. He looked stunned. He listed the rest of his routine, but Connel cautioned him again.

“You may not have time for all that,” Connel said. “When you’re on stage, sometimes you think time seems to be going a bit—”

“Should I just stop at the roundabout joke?” Beamish interrupted.

“Well, no,” Connel said. “When you see the waving light, that’s when you have to stop.”

With his two minutes of practice over, Beamish had more questions. How good was he going to be? Was he going to have enough time to share his funniest material?

“You like that roundabout story?” Beamish asked people in the conference room.

“Yeah, that was really funny,” said Murray, enthusiasm in her voice. It was, however, difficult to tell if she meant it.

A few others in the conference room nodded their heads, too, in what seemed a gesture of politeness. Beamish’s jokes didn’t carry the wit he had expected, but he was inserted into the third slot of the six comics in the live show.

The board of Blue Pencil typically reserved the middle spots for performers who didn’t have experience — and often weren’t as funny.

After 30 minutes, Murray ended the pre-show meeting. Beamish’s run-through ended, too. His live performance on Saturday night laid ahead.

***

Thirty seconds into the set, the mic stops working. Somehow, Beamish has hit the wrong switch. Now, he’s clueless on what to do next.

The audience in The Front Room can hear him, but the sound isn’t as crisp without the speakers amplifying his voice.

Beamish has finished his first joke, an awkward story about when he was a 40-year-old seeking his bachelor’s degree. A few people snicker.

“Is this on?” he asks.

“Hit the little switch,” someone in the crowd shouts.

Flustered, he looks all over the mic and its stand to find the on-off switch. He can’t.

“Oh s---,” Beamish mutters. “This isn’t part of my act.”

The crowd laughs at his desperation.

Lauren Steinkuhl, the show’s host, jumps on stage and flips the switch, which is on top of the mic.

Beamish regroups. He wants to move around, so he grabs the mic from its stand and paces the stage as he begins a joke about being a bad driver. He says he drives 30 mph over the speed limit and, in New York City, cops never pull him over.

“Has anyone been to New York City?” he asks the crowd, now fully tuned into his act.

A woman to his left raises her hand.

“Do they drive fast?” Beamish asks her.

“They drive terribly,” she says dryly.

A few people begin to lean forward in their chairs as they laugh. Beamish smiles. He’s finding his rhythm.

“I drive terribly, too,” he says. “I never stop at stop signs! I go through red lights! I drive down the sidewalk!”

Now, the audience is in hysterics, so Beamish nods and waits a few seconds for the laughter to die.

He tells the crowd he’s received countless tickets since moving to Athens. He rants about how tired he is of seeing people walk across the street with their smartphones out, waiting to be hit by a mindless driver like himself. He also claims cops here are too strict. So instead of driving 30 mph over the speed limit, he drives 10.

“I get so bored,” Beamish says. “Like, it’s so slow! I only drive 30 or 40 on Court Street.”

Laughter fills the room again. Everyone knows that 40 mph is outrageously fast for the narrow strip of red bricks that make up the most famous street in town.

Beamish feigns confusion.

“Isn’t the speed limit 30?”

“It’s 25!” someone in the crowd says.

“Ohhh,” Beamish says. “In New York, we do 60 in a 30, and it’s not a big deal.”

None of that is scripted, but it doesn’t matter. Not to Beamish. The crowd loves him, even though no one knows what to expect from his set.

Then he sees Murray’s light. His time is almost up.

“Oh s---” he says again, generating more laughs. “I only got another minute. Oh God.”

Beamish goes into a joke about a point system he created because of his lack of patience as a driver. He says he awards himself 10 points for making a pedestrian jump with his horn and 20 if he splashes someone with water from a puddle.

As the crowd’s laughter dies, Beamish spots Murray’s flashing light and then looks at his script. He has more jokes to perform, but he doesn’t need to. He’s already a hit.

“Is the five minutes up?” he asks.

They were.

“That’s all I have,” Beamish says. He smiles, turns to the crowd and says, “Thank you.”

Walking off the stage, he waves as the audience shows its approval. Their applause continues a few seconds into the next comic’s set.

No uncertainty came with the ovation. Not this time. The praise was genuine.

“I thought he did very well,” Murray said. “I think people enjoyed him.”