Kendall Adams and her younger sister Annabelle were determined to get out of the nosebleed seats and into the pit for Taylor Swift’s “Red Tour” at the Verizon Center in Washington, D.C. in May 2013.

The two approached one of the tour’s staff members on the escalator and asked if he could move them into the pit. The staffer said moving them up would be a fire hazard.

"We would risk a fire for Taylor Swift,” Adams, a freshman studying communication studies, said to the man.

Adams said she has been obsessed with Swift since the release of “Our Song” in 2006.

"In middle school, I would listen to her every single night without fail before going to sleep,” Adams said. “(Now) if I’m driving, that’s what I’m listening to.”

Almost everyone, young and old, has been a fan of some form of entertainment as the styles and icons in pop culture change. The stereotyped norm with modern pop icons is a fan base with young girls, but it is not uncommon for adults to fantasize over A-list celebrities.

Public display of obsession

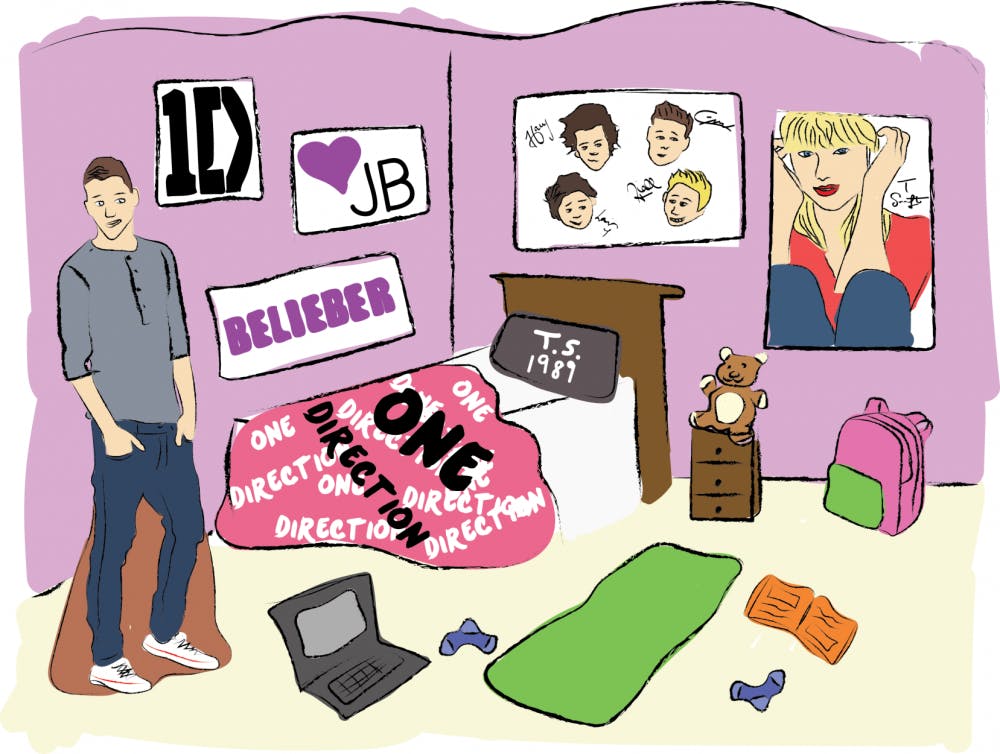

Almost any time Haley Klier sees a One Direction poster in a store, she asks her mother if she can buy it, which usually results in her mother simply answering “fine.”Klier, a sophomore studying business, already has added three posters to her collection since she came to Ohio University.

“They kind of look good,” Klier said. “They just go with my color scheme (in my dorm).”

Klier began liking One Direction when she was in high school and can’t estimate how many times she has listened to the band's songs. She admits to being a Directioner, a term associated with One Direction fan.

“I’m a huge Directioner,” Klier said. “They’re my favorite.”

Klier has been to three One Direction shows — in Detroit, Columbus and Cleveland — and got floor seats each time.

Hannah Pemberton, a freshman studying playwriting, has been a ”Swiftie” — the name of the singer’s loyal fans — since Swift’s first album was released in 2006. She once painted a life-sized portrait of Swift for an art project.

“I remember listening to the song ‘Invisible’ 30 times in a row one night just, like, crying, thinking about a guy that I was in love with,” Pemberton said. “That’s kind of when it all started.”

Pemberton has remained a fan since, though she said she sometimes felt as if she needed to keep her obsession a secret.

“It kind of died down when the media started attacking her (during her transition from country to pop) because I felt almost embarrassed,” Pemberton said. “But I still secretly (listened to her). It was like a guilty pleasure.”

Megan Fogelson, a freshman studying studio art, and Pemberton have been friends since when they first arrived on campus in the fall. Pemberton made her Taylor Swift obsession known the first day they met, Fogelson said.

Fogelson — a fan of Swift but not to the same degree as Pemberton — said every day she is with Pemberton, they listen to the “Bad Blood” singer.

“I think you just let strangers on the street know that you love Taylor Swift,” Fogelson said to Pemberton. “You’re not ashamed of it, and you’ll fight people about it if they say they don’t like (Swift).”

In fact, Pemberton’s pride is seen on her Swift T-shirts, multiple pairs of Keds shoes from the singer’s line, and cat ears and red heart sunglasses — staples in some of her music videos. Pemberton also has acquired a plethora of Swift merchandise — books, magazines and posters — throughout the duration of her obsession.

Pemberton was almost a hair away from Swift at one point. Her friend, knowing about her obsession, admitted to Pemberton one day that his hairstylist was one of Swift’s hair stylists in New York. Pemberton quickly made an appointment during her already planned trip to New York City for spring break. But that slot had been canceled for a higher-priority appointment: Swift.

In defense of infatuation

An obsession may be constructed as a method of channeling passion or as a form of escapism, which is a type of entertainment that allows a person to forget, according to Kelly Choyke, an instructor of record in the Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies Department and a Ph.D. candidate.

It gives people something to look forward to and helps make people content, she said.

“Let’s be honest, life is difficult,” Choyke said. “It’s not always fun. It’s never easy. ... (Fandom) makes life more fun, more interesting and it also brings people together.”

Fanaticism can have negative effects if the obsession inhibits an individual from common functions, such as school or work, Choyke said.

“If it’s not doing that, then I don’t see what the harm could be,” Choyke said.

People can be a fan of many different things, and Choyke said it is interesting how we categorize fandoms.

“We don’t think of fans of Doctor Who in the same way we think of fans of football,” Choyke said. “Although you can say (a person’s) aggressive obsession with something ... you’d see that far more in sports than in fandom of, like, a television show or romance novels or comic books. ... We need to expand our perceptions of what being a fan is.”

Chester Pach, an associate professor of history, said modern fans have more opportunities to interact and experience their favorite artists than they did 50 years ago, but the intensity of the obsession among fans hasn’t changed throughout the past few decades.

In the ’60s, fans of bands such as The Beatles had limited ways to experience their fandom, usually through records or on the radio. Today, fans have platforms, such as Spotify and YouTube, to watch and listen to their favorites whenever they want.

Pach said he once heard a story of The Beatles going to a club in New York City just to dance with random fans.

“Can you really imagine dancing with Taylor Swift today? I can’t,” Pach said.

Stigmas of “fangirls”

Adams said a lot of people at OU are unaware of her Swift obsession because she did not bring any of her posters or other memorabilia to school with her.

“I don’t think there’s any reason (I didn’t bring my stuff to college) besides, like, people are going to think I’m crazy if I bring all of this Taylor Swift stuff,” Adams said.

Bringing memorabilia is different, Adams said, because Taylor Swift is a woman. Mainstream heterosexual norms say it is more accepted for men to have posters of women on their walls and vice versa.

“It’s like, ‘Oh my god, (One Direction is) so hot,’ but Taylor Swift is, like, 'I think she’s awesome and a good role model,' ” Adams said.

When women are infatuated with pop culture icons, they can sometimes be stigmatized in a negative way and be dubbed “fangirls.”

Young women today who are fans of pop icons act similarly to the way young women acted 50 years ago, Pach said.

“It’s amazing the effect (The Beatles) had on young women,” Pach said. “If you look at footage of their concerts ... these young women are screaming. They’re grabbing their hair and jumping up and down.”

Though the passion has remained the same, Pach said the scope has changed because fans can express their fanaticism through social media as well as in real life.

Choyke said she doesn’t think there is anything abnormal about fandoms among adults because they are a part of culture and can be positive.

“Things that people spend their time being a fan of might change,” Choyke said. “I don’t know how many adults cross over into Justin Bieber territory, but I mean, if you look at other things in culture — television series, comic books, romance novels — there are huge fandoms there comprised primarily of adults.”

When it comes to the use of the word “fangirl,” Choyke said the term is meant to enforce the power structure between men and women.

“The term ‘fangirl,’ that assumes that the term ‘fan’ only applies to men and that it’s only mode of legitimacy is men or boys. So you have to have another term to separate or segregate women or girls,” Choyke said. “Girls is a term for young females — it’s not a woman.”

Using the term “girl” also reinforces society’s obsession with youth and is “an excuse to take women less seriously,” Choyke said.

“Any time any person is biologically or culturally designated as female, anything that a woman likes is somehow suspect,” Choyke said. “That’s the way it is with anything. If a woman reads it, it’s not that good. If a woman watches it, it’s not that good.”

Once the “Red Tour” staffer saw Adams and her sister were headed back to the top level of the stadium, he told them to follow him. Adams said she knew following a stranger was not necessarily something they should do, but they did it for the prospect of better seats. The worker then found another staffer who pulled front-row tickets out of his pocket and gave them to the sisters.

“I’m pretty sure I cried,” Adams said. “I called my dad and he flipped out. He thought something was really wrong because I was hysterical.”

@_alexdarus

ad019914@ohio.edu