Belle Knox is hardly a household name. Her plight, however, since assuming the occupation of a pornography actress has been widely followed by the media, online message boards and her classmates at the prestigious Duke University.

Her given name — which we have chosen not to use — has long been outed and published by a number of widely-circulated media outlets. Details of her private life have been exposed, and many know her story.

It goes something like this, according to a gaggle of reports: Knox, then 18 years old, chose to enroll in an expensive private school in hopes of eventually earning an equally-esteemed law degree. She got in over her head financially early in her freshman year, began to run out of options, typed “how to be a porn star” into Google and touched down in Los Angeles about a month later to give it a try. She shot a few films, confided her secret with a fellow student and was soon flooded with Facebook friend requests from her classmates across the Durham, N.C., campus.

What she’s accomplished in the several months since first stepping in front of the camera — aside from legally working her way through school in a field that’s as equally controversial as it is lucrative — is spark a conversation that might not have happened otherwise. One about pornography, a subject that has a following of millions and an academic discipline devoted to its study.

Really, though, why haven’t people been talking about pornography all along?

A Bevy of Opinions

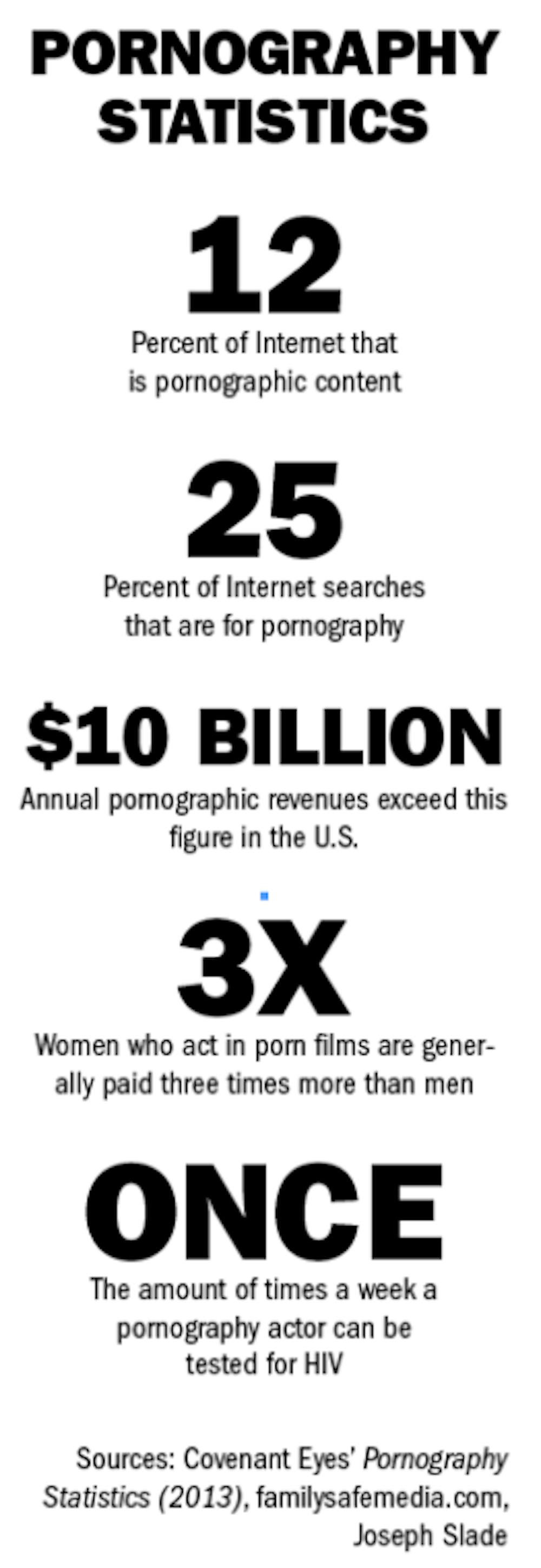

Whether it’s peering into the endless stream of Internet pornography in a basement bedroom as a teenager or flipping through raunchy magazines “for the articles,” almost every college student is familiar with pornography. More than two-thirds of college students had been introduced to the genre by the age of 18, according to a 2008 study, and a study from two years prior estimates about a quarter of online searches are for pornography.

But most don’t often talk about it, for a variety of reasons.

Students selected at random while studying in Baker University Center have a variety of opinions as to why that may be.

It’s embarrassing:

“I do feel like there’s kind of a stigma around pornography, but I also feel it’s natural,” said Madelyn Horner, a sophomore studying communication. “I personally don’t watch porn or anything, but I think it’s kind of an embarrassing thing for people to talk about, but I think it’s natural.”

It’s against my religion:

“I’m a Christian, so from that perspective it’s wrong on every level,” said Josh Travers, a sophomore studying education. “Then, looking at the effects it has, it destroyed marriages.”

It’s deviant:

“I was told it was a sinful thing to do,” said Emma Caldwell, a freshman studying psychology. “So I don’t. I understand why people do. I don’t think badly of other people if they do, because it’s what they do. It doesn’t matter to me.”

It’s a private matter:

“Sex is supposed to be for your partner and stuff, not just to go do and make money,” said Riley Kevil, a sophomore studying sport management. “So I think it’s just looked down upon from normal people.”

“But let’s be honest,” Kevil continued, “almost every guy’s watched it. Probably most girls have watched it. (Actors) make good money doing it.”

Others make a living analyzing, conceptualizing and, yes, watching it, as members of the academic discipline of pornography studies.

A Cultural Obsession

Despite people’s natural tendency to keep intimacy between the sheets, Joseph Slade, a professor and one of the nation’s pre-eminent pornography scholars, said sex is embedded in culture and that its film depictions are “a viable and useful commodity” that can be helpful in analyzing societal trends.

Slade, of the School of Media Arts and Studies, said pornography is a backdrop for Americans’ obsession with appearance and youthfulness and that it also takes on societal trends that can be more telling of us as a people than one would think.

An example: Slade said there is a growing trend of more minority actors being featured in pornographic films — especially Hispanic-Americans, but also African-Americans, Filipino-Americans, so on and so forth — as their populations rise in the United States. That’s because those subsets of the populace are attempting to impress their standards of attractiveness and sexuality on the mainstream, he said.

“(Pornography) is like any other kind of merchandise, where it’s fragmented to the point where you can get exactly the size you want, exactly the color that you want — exactly what you’re looking for,” he said. “So sexual tastes are then developing, whether they’ve been refined or are degenerated. … I think it’s amazing that people are turned on by so many things.”

He likened the rise of widely available online pornography — studies say about 12 percent of the Internet is pornographic content — to the popularization of rap music over the last three decades. Pornography, like other subsets of popular culture, “feeds on its margins,” bringing lesser-known elements of the genre to the mainstream because of their potentially widespread appeal, he said.

Still, the core of pornography’s appeal is its taboo nature and how it’s a reminder of the control one can have over his or her body, Slade said.

That has remained constant over his 40-plus years in the field, during which he has watched somewhere in the neighborhood of 9,000 pornographic films — a total he said could put him among the country’s top viewers.

However, he’s hesitant to distill the overarching message he’s taken away from the years dedicated to the genre.

“Pornography is what it is,” he said. “Does it cheapen sex? I suppose it’s possible. Does it demean women? Sometimes, not always. Is it sort of trashy? Yeah, a lot of the times. Does it waste people’s time? Sure. But for a lot of people it is a source of fantasies, and they help to enliven people’s erotic life, and I think that’s fine.”

An Ethical Dilemma

An age-old debate about pornography is whether it should exist, with one side citing the genre’s demeaning attitude toward women and often poor working conditions and the other championing its ability to empower actors and viewers alike, teaching them a thing or two in the process. Sarah Stevens, a master’s student studying film studies, said the debate should be centered on improving poor aspects of porn instead of pushing for its prohibition.

“What really bothers me about what a lot of people assume about porn in general is that it’s this monolith, that it’s this one thing, and there aren’t factions and subsets and different kinds of distribution and creation and working conditions,” she said. “It’s been created to be this blanket scapegoat, ‘This is this bad thing that causes all these other bad stuff to happen.’”

Stevens studies feminist pornography, a subset of the genre she said has been around since the 1970s and emphasizes performers’ desires and working conditions.

She recently returned to Athens from the Feminist Porn Conference at the University of Toronto this past weekend, where she spoke about altering feminist perspectives of pornography. The conference, which was founded in 2013, is one of a kind, she said, because of the conversations that are fostered among the academics, sex educators and workers who make the trip.

Some of the conversations she was privy to in Toronto mirror are those she incorporated into her OU course “Screening Sex: Intro to Porn Studies” this summer.

In it, she showed pornography every week and taught her students about the history of the genre.

Olivia Bullock, a junior studying geography and East Asian studies, was one of the five students who attended Stevens’ class. She said her classmates came from a variety of backgrounds and areas of study and that she found the class to be instructive, focusing on the artistic aspect of pornography as well as the power and control exhibited in it.

She said talking about large-scale issues reflected in pornography, such as social power and inequality, gives people the opportunity to discuss how those subjects affect the way they interact with each other, sexually and otherwise.

“It’s one thing to be, like, ‘This is my personal life and my personal experience,’ ” she said. “That’s awkward for everyone, I think. But it’s a lot less awkward (than) to say, ‘When I was growing up, a lot of the porn that I watched involved women being degraded or treated in certain ways, and now I don’t know what my girlfriend wants. I don’t want to talk to her about it.’ That’s really awkward.”

The New School

Linda Williams, a professor of Film & Media and Rhetoric at the University of California at Berkeley, is one of the scholars who kicked open the door for academic conversation about pornography — especially among women. She published one of the best-known books about pornography, Hard Core: Power, Pleasure and the “Frenzy of the Visible,” in 1999. In it, she urges readers to eclipse anti-pornography debates that have forever circled the genre and pushes for a more complete history of its works.

She touched on similar topics among a host of others in recently published research that looks to delineate pornography as an academic discipline from the “porn” or “porno” that can be found with only a couple keystrokes.

“The problem with ‘porn’ and ‘porno’ is that it signals, given the context of debates about pornography, an easy acceptance of the genre and therefore precludes debate,” she said.

She said everyone need not understand the study of pornography, but she is concerned that people don’t look at it as a legitimate field of study.

“Will the Library of Congress preserve pornography? It doesn’t. That’s the main problem,” she said.

Slate echoed a similar sentiment, saying he’s been subject to stereotypically disparaging remarks about his line of work. Stevens said she was reluctant to advertise her class, for fear of the class becoming a caricature of itself and attracting a crowd that’s uninterested in actually studying the material.

But pornography, to them, isn’t different than any other field of study and should be considered as such.

“It has emerged as a more or less legitimate form of sexual discourse or discussion,” Slade said. “I think that it’s trying to tell us something, but I’m not quite sure what.”

Addiction & Religion

The message is murky when it comes to pornography addiction.

Less than 10 percent of pornography viewers might consider themselves addicted to the stuff, estimated Joshua Grubbs, a doctoral student in clinical psychology at Case Western Reserve in Cleveland who recently published a study examining the correlation between pornography addiction and religious beliefs.

There is no official clinical diagnosis for pornography addiction, he said. That’s similar to video game addiction — a subjective condition in and of itself — or any other self-labeled dependency.

“If they say they’re addicted, I don’t want to tell them they’re wrong,” Grubbs said. “My opinion is before we jump there, before we say, ‘You’re addicted to this behavior,’ let’s look at what else is going on.”

Some who claim to be addicted, he said, watch pornography only several times a year but consider themselves to be addicted to the behavior — even if that may not be the case.

And when it comes to college students, Grubbs said he hasn’t seen any indication that a higher number are addicted to pornography than in any other demographic. Most college-aged people are, however, more adept at using technology than most, meaning they are bound to be using the Internet for more than just studying and SparkNotes.

And more often than not, his recent research shows, those who are religious and indulge in pornography tend to categorize themselves as addicts more than their non-religious peers.

“They’re viewing it, and their religious beliefs say that’s wrong,” Grubbs said. “How does that make them feel?”

The short answer, oftentimes, is guilty.

An Eternal Interest

Pornography, like any established genre of film, isn’t going anywhere. Rather, it’s expanding, finding new ways to give viewers the “oohs” and “aahs” they’re looking for.

There are fads — films that require 3D glasses and others shot using cameras that catch more than the eye could ever desire — and more evergreen erotica, such as parodies of more popular mainstream media, from Batman XXX to Buffy the Vampire Layer. It all comes down to getting the highest quality image, Stevens said, and parodies and other feature-length films have the biggest budgets to best please viewers.

As the field grows, younger generations are becoming more accepting of it than their older counterparts. According to data from the Public Religion Research Institute, 45 percent of American millennials think viewing pornography is morally acceptable, compared with just 29 percent of the overall population that feels the same.

Still, people are “starkly divided” about pornography, Stevens said. Many are dependent on the multibillion-dollar industry, but equally as many are taken aback when a story such as the Duke student’s hits the Internet.

If her story doesn’t move the conversation forward about pornography, at least it provides a talking point on the topic.

“People have to really assess for themselves what makes them uncomfortable about porn (and) what makes them uncomfortable that a young woman wants to support herself through porn,” Bullock said. “And it makes us ask questions about what about sex do we consider dirty or bad or something to be kept in private? And what is it about sex that really fascinates us, that compels people to still watch pornography?”

The same reason it always has, Slade said: “It’s normal. Sex is natural. People want to see it.”

@jimryan015

jr992810@ohio.edu