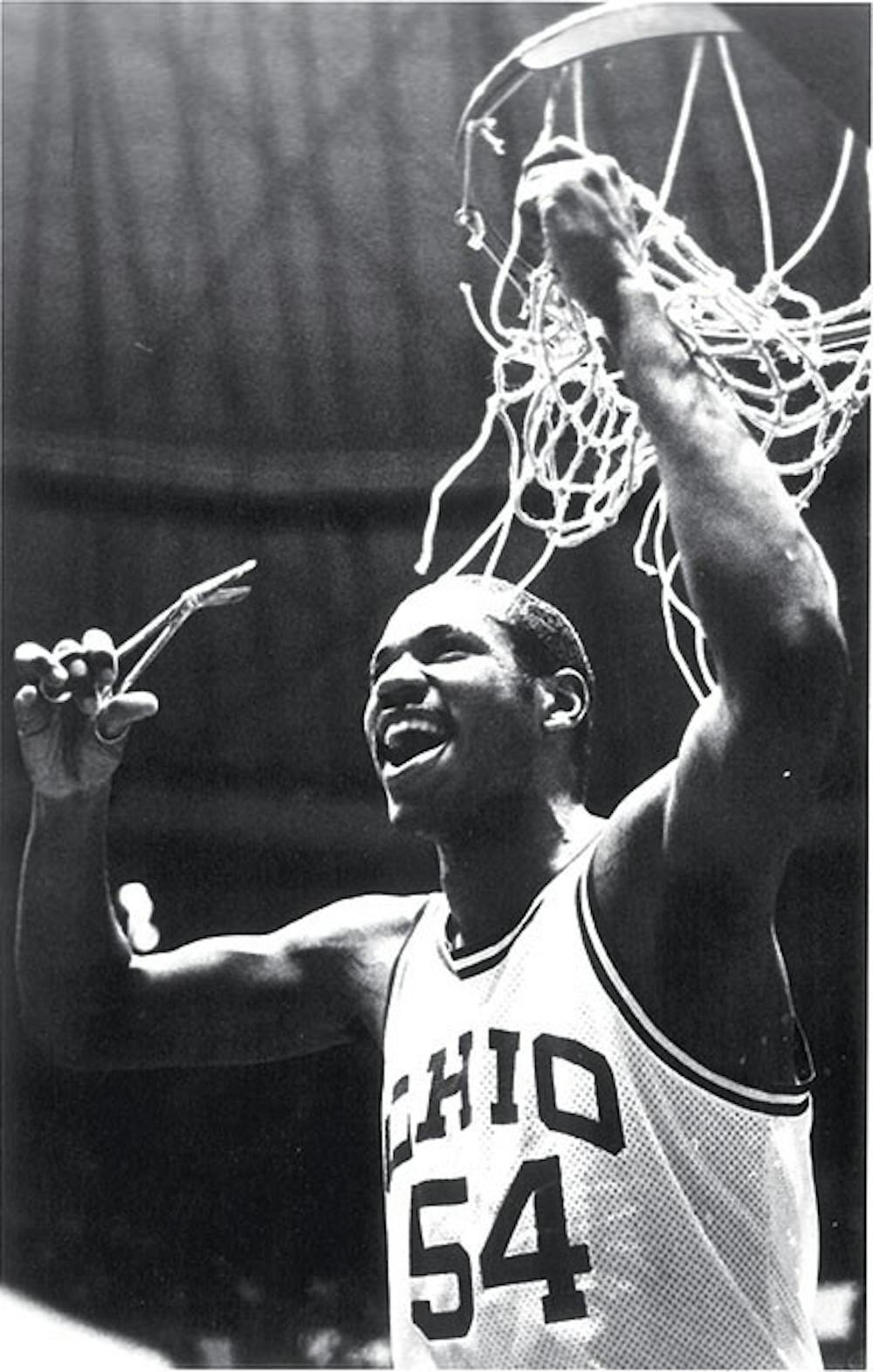

Former Ohio basketball player John Rhodes was walking down the street in Germany with his wife Jackie in 1989 when they were confronted by a crotchety older man.

The man called Rhodes, a current Duquesne assistant coach, a “schwarzer” — a derogatory term for blacks in Germany — and proceeded to spit at Rhodes’ feet.

It took everything in Rhodes’ power not lash out at the man, but he wanted to prove he wouldn’t succumb to the hate or give him the time of day.

That’s a story Rhodes tells his players to educate them about the hardships he faced as he was growing up.

His African-American heritage is something he values dearly, and February is an incredibly important month to him and other athletes and coaches throughout the country.

“It means a whole lot in that I’ve tried to personally reflect on some of the great African-Americans that paved the way for a person like myself,” Rhodes said.

It gives them a month to reflect and remember the people in their past who’ve had an impact on life for African-American’s everywhere.

Ohio defensive line coach Jesse Williams said one of his goals as a football coach is to educate his players so they understand the trail blazed by those who preceded them.

“I try to make sure that the guys in my meeting room have an understanding of the history, the people that came before them,” Williams said. “I think that’s a big bone of contention with a lot of people is that: Do these young people understand the history?”

Ohio senior guard Nick Kellogg said he looks back and appreciates the fight and sacrifices his ancestors made to provide him the chance to play men’s basketball at the collegiate level.

“There’s definitely the people that have come before me and that have kind of paved the way for guys like me to have this opportunity and to do something they love with no barriers,” Kellogg said.

Understanding the history of his culture is also important to Thad Ingol, a redshirt junior safety for the Bobcats’ football team who uses the month to reflect on people like Martin Luther King Jr., Muhammad Ali and Jackie Robinson who have in part provided him the opportunities he has today.

But Ingol said that he is sometimes subjected to stereotypes because of his status as an African-American student-athlete.

“Sometimes we’re looked at negatively because we come from different backgrounds and have different heritage,” Ingol said. “We kind of come off aggressive, maybe thuggish, but really that’s just the way you were brought up, and it’s hard to adapt into something new.

“I hope nobody doesn’t like me because they think that I’m a thug or think that I come from this place or that place.”

Those stereotypes followed Rhodes when he played professional basketball in Iceland from 1991-96. He said that people there expected him to fit their archetype of a typical “black American.”

Rhodes worked to educate those around him that all African-Americans aren’t like those they saw in movies or listened to in rap music.

“There are some people that are intelligent, that aren’t packing, who don’t sell drugs,” he said. “(People) that want to do things the right way in life. And that was me, and that was what I was trying to do.”

Dealing with those stereotypes wasn’t nearly as much of an issue for Rhodes while he was in Athens, as the diversity he felt within the basketball team, the university and the city drew him to play for the Bobcats after graduating from Milwaukee Lutheran.

Other African-American athletes have thought similarly to Rhodes.

Ingol went to Barberton High School near Akron, where the majority of students were white. He felt that many formed negative opinions about the African-American students at his school.

Ingol was instantly drawn to the interaction between students of all races at OU and said that he and his teammates often use diversity as a selling point when they talk to potential recruits.

“Once I was here, I was able to pick a group,” Ingol said. “It didn’t matter if you all were black or all were white. Once you found your group, you were accepted.”

To junior Ashley Cureton, who is the only African-American woman on the field hockey team, being a black athlete at Ohio is no different than being an athlete of any other culture.

“I think our university is very diverse, so it’s like being any other athlete,” Cureton said. “I think it’s important to represent who you are and the black community, but at the same time, I think this university is very well integrated, and everyone’s a big family.”

Phil Wellington, a redshirt sophomore wrestler from Euclid, is the first from his family to attend college and is pursuing a mechanical engineering degree that he says makes his kin proud.

“The opportunity came a lot easier for me than for my relatives,” he said.

And for Wellington, who is one of three African-American wrestlers regularly featured in Ohio’s lineup, when it comes down to competing as a team, the color of his teammates’ skin ultimately makes no difference.

“If you have talent, it doesn’t matter if you’re an African-American or if you’re Caucasian,” Wellington said. “As long as you have the ability to compete, we’ll all band together and put the strongest squad out there.”

@c_hoppens

ch203310@ohiou.edu